What Is Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia?

Introduction to CDH

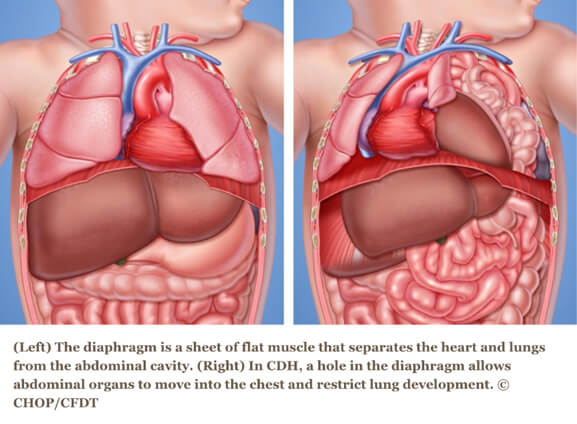

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) occurs when a hole in the diaphragm muscle — the muscle that separates the chest from the abdomen — fails to close during prenatal development, and the contents from the abdomen (stomach, intestines and/or liver) migrate into the chest through this hole.

About 1,600 babies are born with CDH every year in the U.S., or 1 in every 2,500 live births. Each year, the same number of babies are born with cystic fibrosis or spina bifida.

When the abdominal organs are in the chest, there is limited room for the lungs to grow. This prevents the lungs from developing normally, resulting in pulmonary hypoplasia (or underdeveloped lungs). This can cause reduced blood flow to the lungs and pulmonary hypertension (high blood pressure in the pulmonary circulation), as well as asthma, gastrointestinal reflux, feeding disorders and developmental delays.

CDH can occur on the left side, right side or, very rarely, on both sides. It can be life-threatening.

Diagnosis

After a doctor has diagnosed CDH in a pregnancy, the next step is to be referred to a prenatal diagnosis center for additional testing and information. This type of fetal consultation includes a variety of diagnostic tests including a high-resolution ultrasound, fetal echocardiogram, and fetal MRI, meeting with a genetic counselor to review family history, and prenatal genetic testing.

A prenatal diagnosis of CDH often includes the necessity for a mother to relocate to a CDH center for treatment at the last stages of her pregnancy. The severity of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is largely determined by the position of the liver.

Outcomes are generally better in cases where the liver remains down in the abdomen and the LHR is higher. The national survival rate is approximately 70 percent.

Treatment

Often babies require specialized equipment such as the oscillator ventilator, heart lung machine (ECMO) or nitric oxide, but it is important that they have immediate access when necessary.

For babies with the most severe cases of CDH, treatment before birth may allow the lungs to grow enough before birth so these children are capable of surviving and thriving.

Fetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion (FETO) is a fetal surgery procedure that may improve outcomes in babies with the most severe cases of CDH. After FETO, mothers remain nearby until birth. Upon delivery, the baby will be stabilized will undergo the traditional postnatal surgery to repair the hole in the diaphragm.

ECMO

After delivery, babies with severely compromised or fragile lungs may require extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), a temporary heart-lung bypass technique used to oxygenate the blood and allow the lungs to rest.

Under sterile conditions at the bedside and once your baby has received pain medication, two tubes called cannulas are inserted into the artery and vein in the baby’s neck. The tube in the neck takes blood out of the body from the large vein, oxygenates the blood through the ECMO circuit and returns the now oxygenated blood to the baby by the carotid artery.

ECMO is used when other treatments are unsuccessful. The lungs rest as the ECMO circuit does the work. In some cases the baby may have the CDH repair while on ECMO.

ECMO can have serious complications including bleeding and infection. Careful monitoring by an experienced ECMO specialist is critical. Usually, one ECMO specialist and an experienced neonatal surgical registered nurse oversee care at all times.

Postnatal Surgery for CDH

Surgical repair of CDH after delivery depends on a baby’s progress in the days following birth, and can occur as early as three days of life. General anesthesia is administered and is continually monitored by a pediatric anesthesiologist. An incision is made just below the rib cage, the organs in the chest are guided back down into the abdomen and the hole in the diaphragm is sewn closed. The space created in the chest allows the lungs to continue to grow; children will continue to grow more air sacs or alveoli through early childhood.

For babies with large defects or completely lacking a diaphragm, the hole is closed with a GORE-TEX patch or muscle flap. Sometimes the abdominal wall cannot be closed during surgery. In these cases, temporary placement of a silo, mesh or Vacuum Assisted Closure (VAC) device may be recommended. As a child grows, the condition of the patch is regularly monitored by doctors to ensure that it remains intact.

Length of hospitalization can vary widely depending on each child’s response to treatment. As babies receive this comprehensive medical care, families requires help and support from social workers and psychologists.

CDH Outcome

Long-term follow-up by a team of experts is important to provide the best clinical care to your child. Often this includes a team of clinicians from general surgery, developmental pediatrics, pulmonary, cardiology, psychology, nutrition, audiology, social services and others as needed.

Babies with CDH are extremely sensitive to noise and movement. Prolonged hospitalizations and medications can cause hearing loss. They are at risk for pulmonary hypertension (a condition that causes high blood pressure in the arteries), reactive airway disease, chronic lung disease, numerous developmental delays, and failure to thrive.

Intestinal malrotation or obstruction can occur, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common complication of CDH and in some cases requires additional surgeries and procedures, such as the placement of feeding tubes.

This information was sourced from The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). We have included it here for educational purposes only. It is not intended to serve as a substitute for the consultation, diagnosis, and/or medical treatment of a qualified physician or healthcare provider. For additional information about CDH please visit CHOP’s website.